Gender identity refers to an individual’s sense of their own gender. This sense lies on a spectrum of “woman-ness” and “man-ness” and is not always strictly that of a man or a woman, which would be considered “binary.”

Gender Identity And How Understanding It Can Ease Loneliness

Since the beginning of civilization, a wide variety of gender identities and means of expressing them have existed across virtually all cultures.

- There are a variety of gender identities, including, but not limited to, transgender, cisgender, and nonbinary — and a person doesn’t need to express their gender in any particular way in order for their gender identity to be valid.

- Non-cisgender people are marginalized for their gender identities and the ways they are expressed, so to achieve true gender justice, we must move beyond the belief that there can only be two genders.

- Sharing your pronouns with others is a simple act of solidarity that can help to ease transgender and non-binary loneliness.

Struggling with loneliness or having a mental health crisis?

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255); Deaf or hard of hearing dial 711 before the number or connect via online chat

When I was younger, I wanted desperately to be considered “girly” by the people I had crushes on, or simply by the people who didn’t think I could be.

When I was in middle school, I’d get teased for “looking like a boy.”

When kids at school were being particularly vicious, they’d joke that they thought I was a man. (Mind you, I was ten or eleven-years-old.)

I have a pretty high voice, have never been particularly tall, and, until recently, have always worn my hair down to my waist.

I was raised as a girl, and even though I often tried to convince my car and video game-loving older brother to let me hang out with him, some of my favorite cartoons growing up were The Powerpuff Girls and Sailor Moon.

So why the jokes?

One word: hair.

All over my face and body.

My mother told me (affectionately) that when I was born, I was covered in hair.

Real hair – not the peach fuzz that many newborns apparently come adorned with. (I’m Middle Eastern on my father’s side if that helps to clear things up.)

While I’ve made peace with my massive mane, childhood and adolescence were a bit of a nightmare – precisely because I knew I was a girl, even if the kids around me told me that my face and body hair meant I couldn’t really be.

Those who were bullied in school can relate to the loneliness that it caused — regardless of the reason for the bullying.

Even though I haven’t completely gotten past my hang-ups about my all-over hair, this desperation has completely faded, and I now more comfortably express my gender identity in the ways I want to.

I don’t feel the need to put on a façade – through the quality of my voice or the way I dress or by wearing makeup – to prove my femininity when I’m around people I don’t know.

More importantly, the way society views me makes it so I don’t feel compelled to alter my appearance any longer: looking back, my days of being bullied were the product of what some might call an “ugly duckling” phase.

As I got older, my secondary sexual characteristics became more developed, and I learned to better groom my body hair. As a result, the world has continually validated my womanhood.

But what is the experience like for others who are dealing with their own gender identity issues?

As a teenager, I would seldom shy away from heated debates with friends who would casually use misogynistic language they considered normal.

What I didn’t realize being teased while growing up, or during these debates, however, was that I wasn’t considering any experience that wasn’t like my own because, to be honest, I didn’t know any other women whose experiences weren’t like mine.

That is until I met my girlfriend.

My girlfriend and I are both women, but our experiences with gender identity are pretty different.

You might be wondering: “How can that be?”

The answer is simple: she’s transgender, and I’m cisgender – don’t worry, I’ll explain what these mean shortly.

The point I’m trying to make is that up until college, my understanding of gender was limited, to say the least.

I knew that misogyny and sexism informed issues ranging from access to reproductive health care, to pay parity.

What I didn’t understand, however, was that these issues affected many different types of people and not just women like me. I didn’t understand how gender identity — or even the process of fully embracing your gender identity — can result in feelings of loneliness.

Since meeting my girlfriend, I’ve become even more interested in learning about gender identity and expression over the years.

While I took it upon myself to start getting informed for personal reasons, I also realized that there are many reasons to learn about this subject because of its wide reach and effect on those who are often marginalized in much the same way women once were – and some would argue, still are.

My aim then is to give you an overview of gender identity, gender expression, what it means, and why it’s more important than you probably ever realized.

What Is Gender Identity And What Are Some Real-World Examples?

Throughout my learning process, I’ve come to understand that the concepts of gender identity and expression are far from new.

For thousands of years, numerous indigenous cultures throughout North and South America have embraced the spectrum of diverse gender expressions.

India’s trans community, Hijra, has a recorded existence of 4,000 years and was widely respected throughout the subcontinent until British colonists sought to criminalize it in the nineteenth century.

Artifacts found at a burial site in Iran suggest that more than two genders were acknowledged during the Iron Age.

Again, while the existence of gender diversity is nothing new, its normalization in the West certainly is.

Since the mid-2010’s, mainstream news and entertainment media in the U.S. have come to increasingly acknowledge the existence of transgender and nonbinary people – more on what these mean in a bit.

As a result, gendered terminology – and the public’s understanding of gender identity and expression – has slowly begun to evolve.

Gender identity is a seriously expansive topic. While it’s impossible for this article to be one hundred percent comprehensive, I’ll do my best to cover the basics that everyone should know.

Definitions And Examples Of Gender Identity And Expression

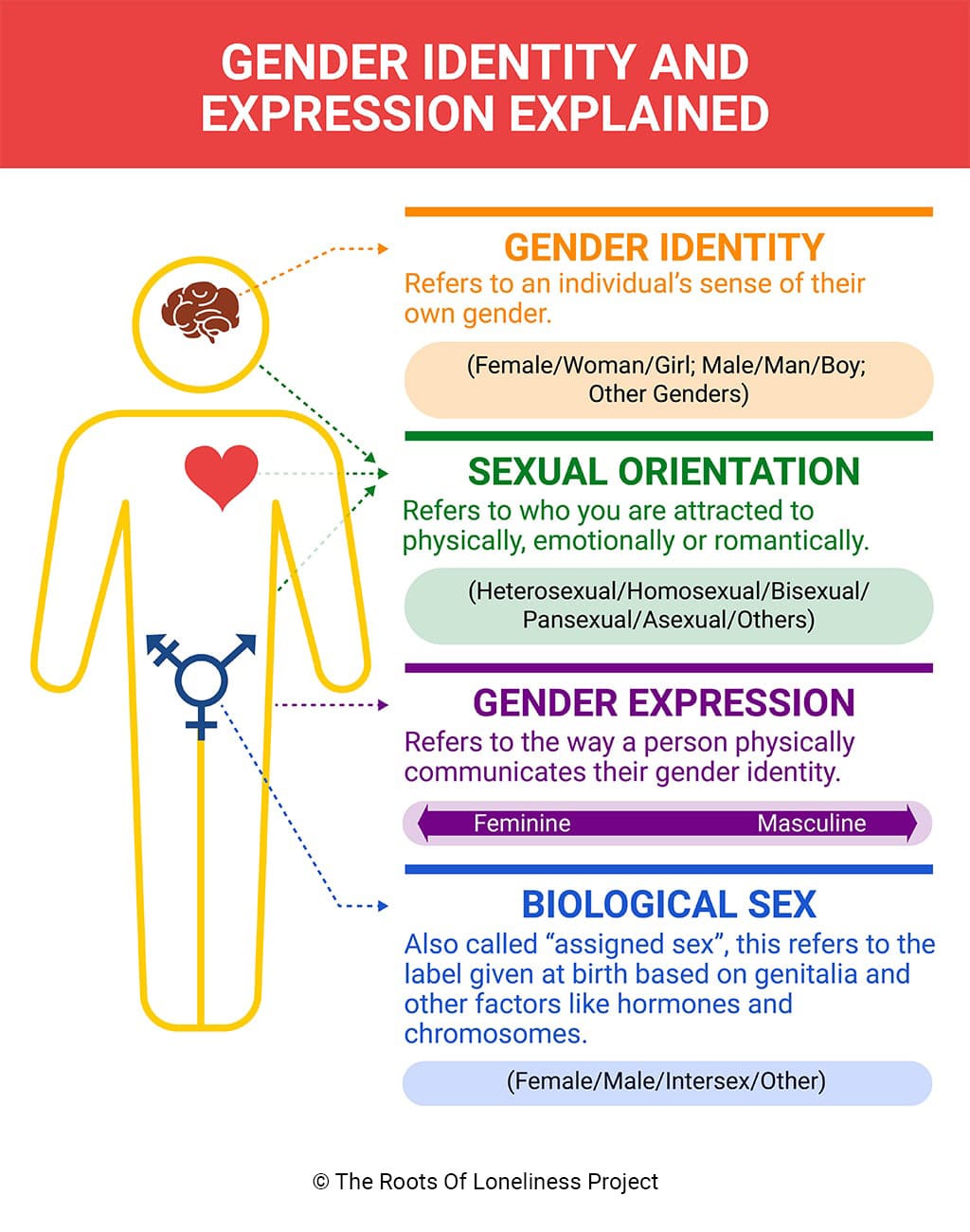

(Click image to enlarge)

Though my girlfriend and I are both women, our experiences with gender identity are very different.

Let me explain. (This section contains a good deal of definitions, so bear with me!)

First, what is gender identity?

The term “gender identity” refers to an individual’s sense of their own gender. Many people identify with the gender identity they were assigned at birth, and many do not.

Gender expression, or presentation, is the way a person physically communicates their gender identity by way of hairstyle, clothing, physique, and so on.

Folks who identify comfortably with the gender they were assigned at birth are considered “cisgender,” or “cis”

Because identifying with your birth gender is considered the norm throughout society, there are many cisgender people who aren’t aware that a term exists to describe their gender identity.

But, as it turns out, no single gender identity is the “default.”

Marie, 33, from Northern California, identifies as a cisgender woman. She tells us:

“I’d never really thought about it until I learned more about non-cis gender identities in college.

I identify as a cis woman, and I’ve never really felt uncomfortable with being a woman. But I also don’t feel like my womanhood is an integral part of me like maybe it is for some other people.”

Transgender, or “trans,” is a general term that describes folks whose gender identities don’t correspond to the genders they were assigned at birth.

The prefixes of both “cis-” and “transgender” have their roots in Latin, and each one references the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender they were assigned at birth.

While cisgender means on this side of, transgender means across or on the far side.

A trans person may identify as binary, meaning they identify as either a woman or man or nonbinary, meaning they feel that they are neither strictly a woman nor a man.

- A person who identifies as either a woman or man is binary.

- A person who feels that they are neither strictly a woman nor a man is nonbinary.

Balian, 28, grew up in the Bay Area and identifies as a binary trans woman.

“I guess being a girl to me is about freedom,” Balian, who was designated a boy at birth, tells me.

I would say that being gendered ‘male’ was all about choices being made for me, and my expressions of femininity are basically the breaking of the mold. If masculinity was restriction, then femininity, to me, is freedom.”

Fe, 27, of New Hampshire, spoke of similar freedom when I asked her what gender expression meant to her.

“I don’t owe anyone a hyper-feminine presentation,” Fe, who is also a binary trans woman, told me.

“I wanna be free to do things that any other woman should be able to do. I wanna be able to only wear pants if I feel like it, and I don’t want my gendered expression to be shaped by people’s expectations of what ‘essential woman-ness’ is.”

Again, many trans people do not identify simply as either “woman” or “man.”

A person who is assigned female at birth but finds later in life that they identify with some aspects of each binary gender, or with more aspects of one than the other, may identify as nonbinary.

There are a multitude of nonbinary identities (e.g., butch, femme, genderqueer, genderfluid, agender, and so on).

We don’t need to list and define each and every one of these identities here; what’s most important is understanding that each one describes a person who identifies as both, neither, or some combination of the male and female genders.

(Click To Enlarge Image)

How Someone Identifies Is Completely Up To Them

Basically what all of this means is that whatever label a person chooses to describe their gender identity is completely up to them!

If a nonbinary person connects more strongly with one gender, they may identify as a nonbinary woman or man, depending on which gender resonates more with them.

In order to understand gender identity, it is helpful to think of gender as a spectrum. On one end is “woman” and on the other, “man,” and many people fall somewhere in between.

For example, a person who feels they are a woman might identify as a nonbinary woman if they don’t feel their gender identity is strictly in line with womanhood.

Some folks might read this description and think, “How can you be both nonbinary and a woman?” Others might be completely lost.

A person doesn’t need to express their gender in any particular way in order for their gender identity to be valid.

As I mentioned earlier, my girlfriend is trans, and I am cis. We are also both binary.

She’s always been athletic, and I can’t shoot (or, more specifically, make) a basket to save my life. She likes keeping her hair short, and I find doing my makeup cathartic.

In other words, we are different from each other much the same way any other two women might be from each other. And while none of these characteristics or behaviors are inherently gendered, society views them through a gendered lens.

(Fun fact: though makeup had been worn by men for thousands of years, it was only during the 20th century that it became “women’s” territory – at least in the West.)

Ultimately, when it comes to my girlfriend and I both being women, neither of our gender identities or ways of expressing them are invalid.

While all trans and nonbinary folks share the experience of not being cisgender, not all nonbinary people identify as trans, and vice versa.

Remember Balian and Fe from above?

Both are trans women, and identify as binary.

Likewise, there are plenty of folks out there who identify as nonbinary but don’t identify as trans. It’s all about what works for the individual.

It’s also important to remember that each culture has its own language for defining gender identity.

Since the beginning of civilization, a wide variety of gender identities and means of expressing them have existed across virtually all cultures.

So…Where Do Pronouns Come In?

Since pronouns (she/her/hers, they/their/theirs, etc.) are often tied to gender identity, if you are unsure of a person’s pronouns, it is best to ask them rather than making assumptions based on their appearance, voice, name, and so on.

When my girlfriend and I go out into the world, people often recognize that she is a woman.

However, others occasionally misgender her – meaning they use language that doesn’t accurately reflect her gender identity.

The clearest indication that she is being misgendered is via pronouns (that is, people use “he,” “him,” or “his,” when my girlfriend uses “she,” “her,” and “hers”).

These misunderstandings (at least the good faith ones) are likely based on cues people feel they are reading from her physical presentation, such as her clothing or the way she’s wearing her hair.

I drive almost every time we go out, and nine out of ten times, she cooks for us.

Of course, misgendering someone may be an honest mistake.

However, instead of just swiftly moving on, it might be better to consider what it’s like to walk in the shoes of someone for whom misgendering is a regular occurrence, rather than a one-off.

Imagine if for every person who called you – if you’re a cis woman – “ma’am,” another called you “sir.” You would most likely question – and even come to resent – the qualities you suspected were causing people to believe you were a man.

Not only that, but navigating the social world under these circumstances would be a very lonely road, indeed.

Again, honest mistakes happen.

But it’s also important to remember that there is no “default” gender and that the language we use to label, or when interacting with others, may be impactful to them – even if we didn’t mean any harm.

Although pronouns aren’t inherently gendered, some advocates for gender-inclusive language suggest using “they, them, theirs” when there is a doubt as to which pronouns a person uses.

As our language for gender identities evolves, so does our language for addressing others. This means that a person might go by any one or combination of a variety of pronouns.

Again, if you’re unsure of a person’s pronouns, just ask (politely)!

Because I work from home, a good deal of my professional correspondence takes place via email.

In my initial interactions with clients and editors, I always make sure to include my pronouns beneath my signature, and I’ve encountered a handful of editors who do the same.

This practice is harmless and takes virtually no effort. It also serves as a reminder that we shouldn’t rush to make assumptions about the people around us.

More importantly, however, is the inclusiveness it projects. No one enjoys feeling singled out — we all want to belong. Including your preferred pronouns is an act of solidarity with those who may, deep down, need it the most.

Again, it’s important to note that gender identity, expression, and pronouns are inherently personal and determined by what the individual feels is true for them.

While pronouns aren’t inherently gendered, a person’s pronouns are often tied to their gender identity.

If you’re unsure of which pronouns a person uses, politely ask them.

Why Is Gender Identity – And Understanding It – Important?

While I do think about my girlfriend’s gender identity now more than I did before she came out to me as trans, I don’t know if I’d consider it one of her especially defining characteristics, and I think she’d feel the same.

In fact, there are many people who would not consider their gender identities the most interesting parts about themselves.

However, even today, we continue to debate people’s rights to decide not only how they should, or are allowed to be addressed, but also, how they are allowed to move through society.

This includes whether trans and nonbinary people are able to safely use public restrooms, access adequate and competent health care, and so on. It is the very rejection of these legal and social rights that centers them.

In other words, if the rights of trans people around the globe weren’t constantly being scrutinized and denied, it is likely that non-cisgender identities wouldn’t be as politicized as they are today.

Though I cared a good deal about trans issues and rights before I knew my partner was trans, I didn’t have quite the same secondhand understanding of what it means to be a trans woman in the U.S. as I do now.

Simple things, like introducing ourselves to new people or using public bathrooms, quickly became tricky and sometimes frightening experiences because some strangers became angry upon noting my girlfriend’s gender presentation or that we are in a relationship.

Sadly, the phenomenon of having your identity politicized is a reality for many marginalized groups of people.

Take, for example, cisgender women in the U.S.

From voting to bodily autonomy, the identities of cis women have long been highly politicized in America.

However, these women have not chosen to be politicized for their cis womanhood; rather, this politicization is foisted upon them by the denial of their legal and social rights.

A great example of this politicization is the continual fight for more comprehensive reproductive rights in the U.S.

Significantly, though this topic is popularly understood as a “women’s rights” issue, it’s just as pertinent to many trans men and nonbinary people.

Unfortunately, there are many trans men and nonbinary folks who, despite being able to become pregnant and give birth, are woefully underrepresented in mainstream discussions about reproductive rights.

The kind of social ostracization that trans and nonbinary people are faced with today as a result of their gender identities leads to significantly lower levels of employment and support from family and friends.

Rigid gender norms do not just hurt trans people; they are harmful and limiting to all people because no one fits neatly in a box when it comes to gender identity and expression. Transgender individuals often struggle with loneliness as a result.

For example, a June 2014 study found that 19% of child sexual abuse cases were committed by a woman in a position of trust.

Despite the trauma that often results, public perceptions that minor boys are “lucky” for, or unharmed by, such abuse stubbornly persists today.

Ultimately, if we want to ensure true gender equity, taking the time to question the structural effects of gender norms is necessary – regardless of where on the gender spectrum we identify.

Is There A Brain-Gender Connection?

Modernly, scientific research about the “trans brain” is abundant.

In recent years, numerous researchers have released studies that demonstrate that binary trans women have “female” brains.

While such scientific efforts may be made in good faith, they can serve as harmful ammunition when it comes to influencing the public’s ideas about which gender identities are valid.

After all, how many people do you know who’ve had their brains scanned in order to verify their gender identities?

Put another way, we don’t require that cisgender women prove their brains function like the “average” woman’s before they are allowed to be considered women – and why should we?

If this metric sounds ridiculous when applied to cisgender folks, the research on the brains of trans folks should have the same ring to it.

Again, these studies may be well-meaning. However, they ultimately serve as evidence of our deeply entrenched – and regressive – societal biases when it comes to gender.

Still, other studies, like this analysis of 1,400 brains from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, debunk the myth of the binary brain.

According to the December 2015 PNAS study, “brains with features that are consistently at one end of the ‘maleness-femaleness’ continuum are rare.”

The authors of the study further take care to note that “human brains do not belong to one of two distinct categories: male brain/female brain.”

Scientific studies that categorize the brains of trans people as either “female” or “male” have been criticized by trans activists as lacking objectivity and being rooted in cisgender bias.

As mainstream society comes to acknowledge genders that exist outside the cisgender woman-man binary, such criticisms will hopefully come to hold more water within the scientific community.

It’s impossible to say when – or whether – research will catch up to the reality of gender diversity.

Regardless, it’s worth noting that scientific interpretations of trans (and, more generally, marginalized) folks throughout history have been shaped by cultural biases.

Modern scientific findings on the brains of trans people are varied, and some reinforce society’s harmful cisgender biases.

Ultimately, it is important to remember that gender identity is not determined by biology.

What About Sex And Gender — Are They The Same?

We’ve long based gender on the genitalia that is visible at birth.

In most states, this standard, which dictates that “sex” and gender are one and the same, hasn’t changed.

A person’s “biological sex” is made up of a number of factors, such as their visible genitalia, secondary sexual characteristics, chromosomal and hormonal makeup, and any other reproductive organs they may have.

So why do we rely on genitals to determine a newborn’s sex?

The answer is simple: other than secondary sexual characteristics, we can’t see the other factors (without prenatal testing, that is).

Interestingly, our current method of gendering leads some of us to make surprising discoveries about our anatomies later on in life (more on that below).

Since learning about this system, I’ve wondered what my own hormonal profile might look like. What if I found out that I had higher-than-expected (for a cis woman my age, that is) levels of testosterone?

Should I consider myself less of a woman? Should I start expressing my gender identity differently? What amount of our genders depends on genitals?

According to this system, we’re usually expected to behave according to certain norms based on our assigned sexes.

For example, a person’s being born with a front hole or vagina is typically accompanied by the expectation that they will be attracted to cisgender men, interested in marriage, and have a superior knack for childrearing and homemaking.

According to a September 2017 article in Scientific American, most people “are hybrids on a male-female continuum.”

However, less than a century and a half ago, Scientific American was singing a different tune.

In 1895, the magazine published an article by renowned French surgeon Just Championnière in which he validated the widely held belief that cisgender women are physically weak.

For the piece, Championnière wrote that a woman “should remember her sex is not intended by nature for violent muscular exertion…her speed should never be that of an adult man…”

In other words, physically strenuous activity was, by nature, the exclusive domain of cisgender men – at least according to Championnière.

While stereotypes like this have since been debunked many times over, they’ve had a lasting impact on society’s perceptions of gender roles.

Championnière’s sentiment – and that it was published, likely without much pushback, in a scientific magazine – demonstrates that scientific theory is given to the whims of cultural norms.

According to the 2017 article, however, contemporary researchers found XY chromosomes in a 94-year-old woman and a womb in a 70-year-old man and father of four.

Assuming both have lived their lives as cisgender folks, do these biological revelations automatically change their gender identities?

It would be interesting to hear what Championnière – or, more pertinently, folks who still cling to some variation of his beliefs – would have to say about these folks and others like them.

It’s important to remember that contemporary scientific research is not always rooted in fact. Rather, it is mutable and often influenced by cultural norms.

Many people today would find the claims made in Championnière’s piece extremely ridiculous for how sexist they are. However, in 1895 America, they were more than likely accepted as fact.

So how can we learn from this kind of hindsight when it comes to gender identity?

Though the construction of biological sex continues to be viewed as objective truth, minimal research reveals that it has been long subjected to society’s biases about gender. (If you’re in doubt, feel free to read the Scientific American article linked above.)

In other words, today’s scientific findings about gender and sex will likely evolve drastically ten, twenty, and one hundred years from now.

Perhaps (and hopefully) a decade from now, biological scientists in the U.S. will have ceased trying to force human beings into two narrow gender classifications: man or woman.

Again, gender identity is decided by the individual – not by the latest scientific study.

And a person’s “sex” (or, more accurately, their genitals) does not determine their gender identity or how they express it.

Gender and sex aren’t the same. Furthermore, today, many argue that “sex” is an outdated social construct, rather than a useful designation based on scientific fact.

So, What Does Determine A Person’s Gender Identity?

As illustrated in the examples of my and my girlfriend’s being misgendered (and my constant need to be seen as “feminine” while growing up), rigid distinctions between gender based on biology, appearance, birth name, and so on are infinitely harmful to folks who don’t fit into society’s normative ideas about gender.

While these distinctions aren’t particularly harmful to cisgender people (like me), they have still long pushed large swaths of people to the margins of society by legal means, medical science, and so on.

It’s important to understand, however, that a person’s gender identity is not determined by whether they struggle to claim it.

That many non-cisgender people have difficulty comfortably claiming and expressing their gender identities openly only speaks to mainstream society’s limiting biases about gender.

Put another way, you don’t need to feel uncomfortable with your gender identity in any way in order for it to be legitimate. Your gender identity is real if you decide it is, regardless of how others think you should identify.

Finally, if you find that the gender identity you have claimed isn’t right for you or you’ve changed your mind about how you identify, that’s okay, too.

Understanding your gender identity and how you express it may require a good deal of exploration. There is no time limit or age restriction when it comes to understanding your relationship to gender.

Gender identity – and the way you choose to express it – is inherently personal.

In the end, no one can dictate your gender identity but you.

Societal biases about gender derive from our legal system, medical science, and culture at large.

While these facets of society have long dictated that there are only two genders, only the individual can determine their gender identity for themselves.

Closing Thoughts

In today’s world, more and more people are making the choice to openly claim and express their gender identities, and that isn’t likely to slow down as time progresses.

Realistically, even those who are well-versed on the ins and outs of gender identity had to learn the terminology at some point.

So if you aren’t an expert yet, that’s okay.

Within any kind of cultural evolution, there will be trial and error, and that, of course, means the potential for hurt feelings is vast.

Ultimately, regardless of how you identify, what matters most is that you take a compassionate and respectful approach to learn about identities, expressions, and experiences that might be different from your own, or that you might not be familiar with.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of The Roots Of Loneliness Project, the first-of-its-kind resource that comprehensively explores the phenomenon of loneliness and over 100 types we might experience during our lives.

Find Help Now

If you’re struggling with gender identity loneliness, we’ve put together resources to meet you wherever you are — whether you want someone to talk to right now, or are looking for longer-term ways to help ease your loneliness.

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255); Deaf or hard of hearing dial 711 before the number or connect via online chat

- Resources & Emotional Support For Loneliness

- Volunteer & Pet Adoption Opportunities