Disabled And Lonely: Why We Often Feel Alone And How To Cope

“Laying on my couch on a beautiful day because my body is attacking itself is one of the loneliest things I have ever felt.” — Rachel Burnett

Your friends are supposed to be there for you when you need them the most — but when you have a disability, friends tend to disappear.

- Studies suggest that being disabled, with or without chronic pain, can make you more likely to be lonely than your able-bodied peers.

- Disability is a constant in many people’s lives, and living with unpredictable or invisible symptoms and feeling unsure about how to express what you’re going through are major reasons many disabled people feel lonely.

- For disabled people, however, isolation can be both a choice we make and a result of widespread inaccessibility and a lack of acceptance from society as a whole.

Struggling with loneliness or having a mental health crisis?

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255); Deaf or hard of hearing dial 711 before the number or connect via online chat

Rachel Burnett is a young woman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

She was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the age of nine. Though she’s now in her early twenties and has learned to live with her condition, Rachel still finds it hard to watch friends come and go.

“I have to cancel plans with friends a lot and usually by the second cancelation, they are fed up with my flakiness due to my disability,” Rachel tells me. “It’s hard to blame them, but I wish people would understand.”

For Markus Horner, a 70-year-old man born with Tourette’s, OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder), and ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), finding friends and connecting with others was always difficult, especially since he wasn’t diagnosed until he was in his forties.

“My childhood was not something to brag about,” Markus tells me.

“Since I had all kinds of tics, I was the proverbial pariah. I was constantly avoided and made fun of. Dating in high school was virtually a non-existent activity for me. The only time I could get a date was when it was from someone from another part of town who had never heard of me.”

I’ve experienced various challenges as a disabled person, but I’m lucky to have made close friends who have stuck with me. Still, one of the hardest parts of being disabled has been the loneliness.

One of my clearest memories of loneliness related to my disability occurred when I started college.

When I arrived at my university for orientation a few days before classes started, I was equal parts excited and nervous.

The last several months had been a whirlwind — I had been diagnosed with POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota in March; was working on finding out what medications would work best for me; graduated high school; and prepared myself for college.

Now, I was finally here.

Following my doctor’s advice, I had requested accommodations for college — things that included a single room to ensure I could get enough rest and sleep, a shower that I could fit a shower stool in, and more — to help me manage day-to-day life.

I thought I was prepared.

As it turns out, I wasn’t.

New to advocating for myself and still a bit in denial about what I could and couldn’t do, I went through the first day of orientation pushing myself and feeling deeply lonely.

While everyone around me got to know their roommates, I had no one to talk to. Though I did my best to befriend others, it was hard, especially with the combination of social anxiety and struggling with an invisible illness that meant I looked healthy.

When it began to rain after our official welcome to the university, the two guides for my dorm hall encouraged us to run back to our dorms.

I knew this was a bad idea; running to our dorm would involve a mile or two hilly trek in the pouring rain.

Staring down at my flip flops, I said nothing, despite my reservations and fears. Instead, I ran into the darkness with others from my dorm, unsure how exactly to get back.

While running in the rain might not have been a big deal for someone who was able-bodied, it was not a good idea for me.

Somehow, I made it — if you’re unfamiliar with POTS, this sort of overexertion can be very dangerous.

As I stripped off my clothes heavy with water, I could hear laughter from people across the hall as they made plans about what parties to attend that night.

Looking around my dorm room, now covered with posters and photos, the silence threatened to swallow me whole.

I called my mom, begging to go home.

At that moment, I was prepared to pack up and leave, willing to do anything to get away from the rush of sadness and loneliness I felt.

Why are disabled people often so lonely — and what can we do about it?

How Is Disability Linked To Loneliness?

When you’re living with a disability that affects you every day, life can be lonely, whether you’re a young child, a senior, or somewhere in between.

As a disabled person, I’ve experienced loneliness firsthand on many occasions.

Since I live with chronic pain, I — and others like me — are more at risk to experience loneliness.

Though many studies primarily focus on elderly populations with disabilities, studies still suggest that being disabled, even without chronic pain, can make you more likely to be lonely than your able-bodied peers.

A big reason disability is linked to loneliness has to do with isolation and finding meaning in your life outside of your pain and isolation.

Dr. Dana Wasserman, a psychologist from Vancouver, British Columbia, has experience working with disabled patients.

She also is disabled herself and understands why isolation is so common in disabled patients. She tells me:

“I have observed when working with clients with disabilities as well as having a disability myself that isolation is the primary challenge. With isolation, people lose their connections to others, and if anything, humans are meant to relate and connect.”

Though it sounds obvious, when you are disabled, you’re the only one experiencing what’s going on in your body.

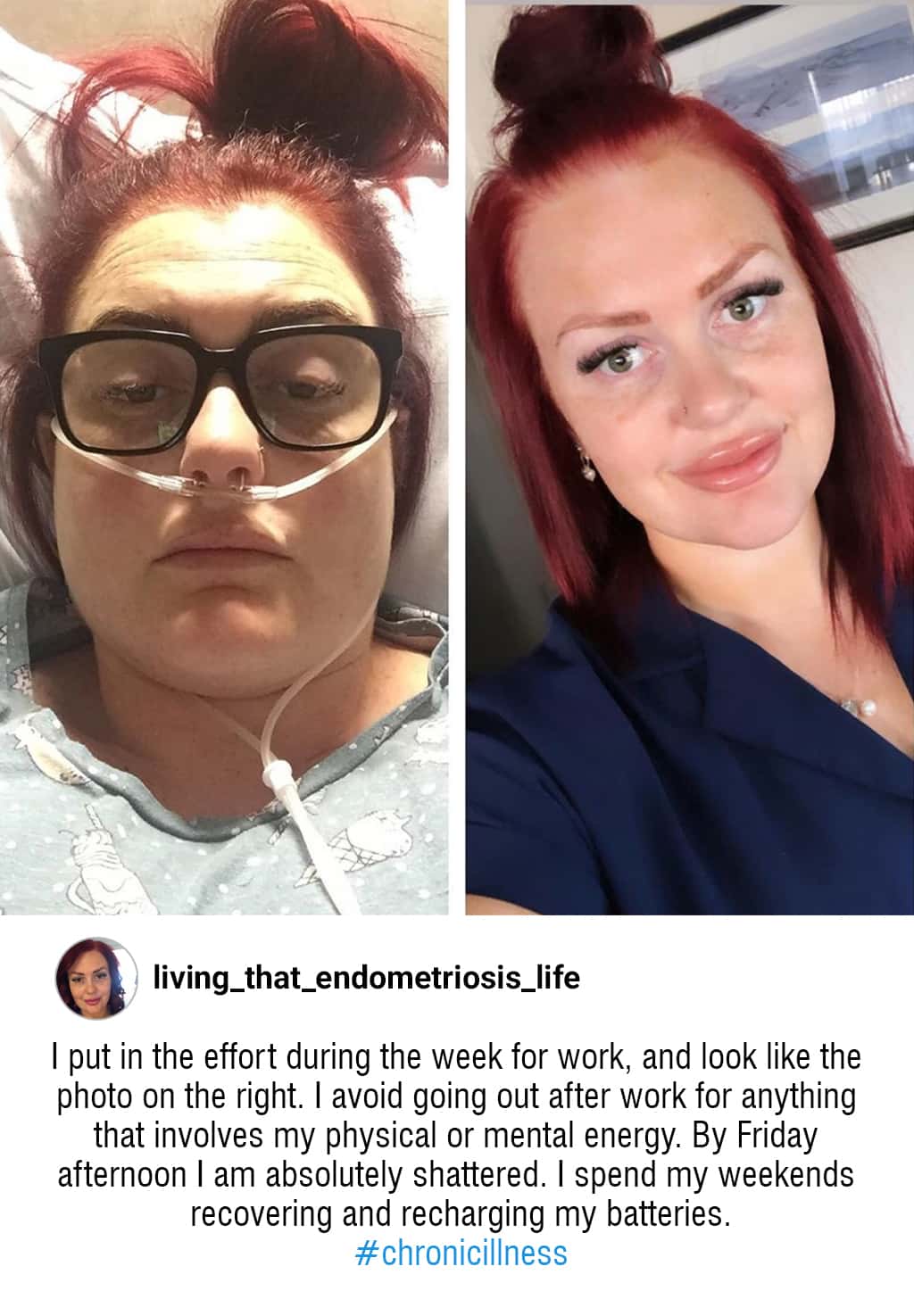

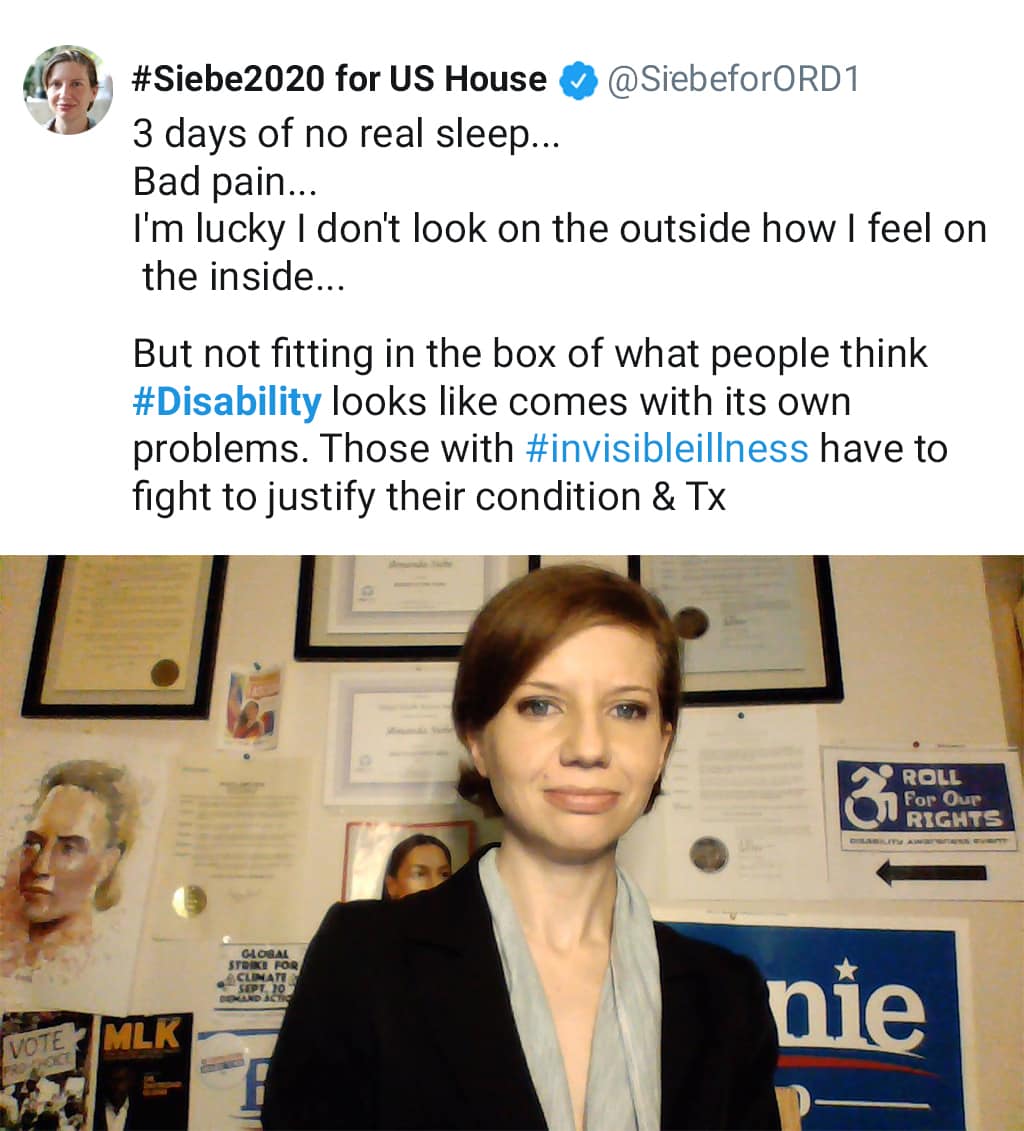

When symptoms such as pain, nausea, fatigue, or dizziness can’t be seen, it can be hard to express the toll disability takes day-to-day.

Rachel, a young woman who lives with Crohn’s disease, says that she has felt in the past that she had to hide the severity of her symptoms, which only made her feel more lonely and anxious.

She tells me: “Every single day is different with a chronic illness and a disability that people can’t see. I find myself trying to downplay my symptoms because I feel guilty for canceling plans or missing work because they are so bad.”

Even on your good days — or even on what should be your best days, like the day of your wedding or the day your child is born — disability never takes a break.

It’s a daunting topic to discuss, and something you may avoid talking about with your loved ones.

However, having to hide your symptoms or avoiding honest conversations with others about your disability can often make you feel more lonely.

Disability by its very nature, is, unfortunately, often lonely — even when people see your disability as an inspiration because you “somehow” manage to live your life.

When you don’t know how you’ll feel on a given day and avoid making connections with other people, it can make you feel as if you’re facing the world alone.

What Causes Disabled People To Become Isolated?

Disabled People Sometimes Isolate Ourselves

Loneliness and isolation often go hand-in-hand, and it can be easy to isolate yourself if you’re disabled.

When you have the flu or a cold, you’re supposed to avoid other people to make sure others don’t get sick. When you feel bad physically, it’s almost instinctual to isolate yourself.

With a disability, though, the same principle doesn’t apply.

A chronic condition won’t disappear after a week or two, and you can’t spend your whole life hiding away even if that’s what you feel like doing some days.

Although I’ve been disabled for the better part of a decade, I still struggle not to isolate myself.

Sometimes, when I’m especially symptomatic and can’t stand the idea of being around others, I choose to isolate myself.

In some instances I’ve had the energy to spend time with others but had to choose between schoolwork or my job, and hanging out with friends — without the energy to do both, working or studying usually won.

Carolanne Monteleone is a young woman in her mid-twenties from Pennsylvania.

She has a variety of conditions, including gastroparesis, anxiety, and dysautonomia, and she also makes a conscious choice to isolate herself sometimes.

“I’m accidentally isolated all the time, as I’m home 99% of my life,” Carloanne tells me. “Sometimes when friends want to hang out and I don’t have the emotional or physical energy, I purposely isolate myself.”

Even though isolating oneself is a tempting strategy to cope with the world and avoid feelings of hurt, isolation isn’t really a healthy coping mechanism according to studies.

Regardless, knowing that I shouldn’t isolate myself doesn’t always prevent me from doing so.

I often worry that I’m going to feel unwell when spending time with friends or family, and I hate the thought of having to leave or cut a hang-out session short.

From my experience, though, even when I do start to feel bad or if I have to leave my friends or family members earlier than I’d like, I almost always am glad that I spent time with other people — and when I’m tempted to isolate myself, I remind myself of this.

Society Often Isolates Disabled People

While it’s easy for us disabled people to isolate ourselves, societal issues can also cause disabled people to be isolated (or “othered,” which I discussed in my article about inspiration porn).

When you’re treated as inherently different, it’s hard not to feel isolated.

Having meaningful connections with other people can help to alleviate loneliness.

However, if you can’t access the restaurant where your friends want to meet due to lack of reliable public transportation, then you’re still left isolated — even with the energy to go out and caring friends who want to see you.

Likewise, if you can’t afford to spend money on social outings — something many disabled people face, since disabled people make an estimated 37% less than our able-bodied peers — then isolation, and loneliness, are almost inevitable.

John, a middle-aged man born with glaucoma, has been visually impaired since he was born, and has experienced different challenges when it comes to connecting with others.

His service dog, Sparky, helps him to navigate the world safely.

Though the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) permits individuals to bring service dogs to public places, so long as the dog is performing a task that aids its handler, many people with service dogs have been denied access to public places.

John tells me:

“Taxi companies and restaurants, in particular, can be challenging [to access]. In a restaurant, my approach is usually to explain that Sparky is a guide dog and under law has a right to accompany me. This usually works, where it doesn’t I’ll ask to speak to the manager. Quite often it comes down to junior staff not being sufficiently trained in the law.”

Not being able to access a place that your able-bodied friends have access to is a horrible feeling.

Suddenly, you’re very aware of your disability, and although the onus of making the world accessible shouldn’t fall on disabled people, it often does.

Another common issue many disabled people face, particularly younger disabled people or people with invisible disabilities, is encountering people who don’t believe they are really disabled.

Carolanne, a young woman from Pennsylvania with a multitude of chronic illnesses, says that she feels lonely when she feels as if she has to prove that she’s disabled to friends, family, and even doctors.

In particular, some people don’t understand why she has a feeding tube, which she uses to receive adequate nutrition since she can’t consume enough nutrient-dense food to thrive. She explains to me:

“I feel like I have to justify myself all the time [because] I look perfectly healthy. Even my own extended family doesn’t understand at times! The worst is having to justify needing my feeding tube to doctors who aren’t my gastroenterologist. They see a healthy BMI (body mass index) or weight and think I can ‘get rid of the feeding tube.’”

Rachel, who is also from Pennsylvania, lives with Crohn’s disease and has also struggled with isolation as a result of her disability.

She says that there are certain people in her life who haven’t been willing to learn about her condition — instead, they prefer to discuss less personal, more exciting topics. She tells me:

“It’s isolating to have a disease that not many people care to learn more about because it is a “bathroom disease” and isn’t as glamorous as some more prominent issues. Laying on my couch on a beautiful day because my body is attacking itself is one of the loneliest things I have ever felt.”

Rachel’s experience, unfortunately, is not unique.

One study in the United Kingdom suggests that two-thirds of British people feel uncomfortable talking to disabled people.

In some cases, this discomfort can lead to relationships falling apart, and sometimes, the relationship never even starts if an able-bodied person is too anxious to approach a disabled person at all.

Even though the world is slowly becoming more accessible for and understanding of disabled people, there is still so much progress that needs to be made.

For those of us with a disability, that means fighting against stigma and inaccessibility in order to keep ourselves from being isolated.

A Combination Of Societal Isolation And Isolating Oneself

In many cases, disabled people are lonely due to a combination of self-isolation and societal isolation.

A negative experience that may stem from inaccessibility can lead us to make the decision to hide away from the world — sometimes, avoiding social interaction altogether seems easier than fighting against a world that wasn’t made for you.

John, who is visually impaired and works in tandem with Sparky, his service dog, has felt the ramifications of inaccessibility, which sometimes makes him feel hesitant to reach out to new people.

“Having a disability can leave me feeling very isolated, like the world isn’t made for me and I am alien to it,” John tells me.

“It’s also really easy to feel like a burden to my family and friends at times. In particular, having a visual impairment plays into social situations, and it can be hard to interact with people when you don’t pick up on eye contact, body language, etc. This can lead to real anxiety around forming friendships and relationships.”

Alan Snyder, a physical therapist who runs his own orthopedic practice in New York City, says that he commonly sees disabled people struggle with emotional and societal barriers.

He tells me:

“Non-disabled individuals who are lonely usually lack motivation and encouragement. Their mental state is their most limiting factor from getting out of the house and reducing their feelings of loneliness.

When a person is physically disabled, they literally lack the ability to interact in the community like they used to. They become fully or partially dependent on others for help.

Being in New York City, my patients have severe anxiety about taking the subway when they’re injured because they are afraid of being dependent and lacking the strength, balance, and ability to simply ride a train.”

The combination of isolating yourself and being isolated by society can create the perfect storm that leads disabled people from all backgrounds to feel immensely lonely.

Being prone to loneliness is just another added challenge that often comes with having a disability.

When isolation comes from ourselves and the world around us, it can take its toll and easily lead to loneliness.

How Can Disabled People And Our Loved Ones Lessen Our Loneliness?

Even though disabled people are likely to be lonely for a variety of reasons, there are steps we can take to try to stop ourselves from becoming consumed by loneliness and isolation.

Carolanne, who has gastroparesis and several other chronic illnesses, finds that spending her time doing things she loves is important.

Though she can’t work a traditional job, selling items on her Etsy shop to help others with chronic illnesses, connecting with other people with disabilities, and spending time with loved ones helps her to feel less lonely.

She tells me:

“I feel happiest when I’m doing something I love. Whether it’s binge-watching a new show on Netflix or getting out of the house to shop, making time — and using precious energy — to do specific things that make me smile is 100% necessary!

I connect with others primarily through online support groups and form friendships with people who understand what it’s like to be me.”

Like Carolanne, I’ve also found that talking to people in online support groups — such as Facebook groups for people with POTS or EDS — and finding people to follow on Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr by looking up popular hashtags, such as #disability or #disabled, helps me to feel less alone.

It’s also incredibly helpful for me to trust the doctors I see enough to be open and honest with them when I’m struggling.

In addition to finding things to enjoy, able-bodied people can also play a part in helping disabled people feel less alone.

Maisy McAdam, a young woman who lost her sight at the age of 15 due to a brain tumor, says that making a point to include disabled people consistently is also helpful. She says to me:

“Able-bodied people can just help by making sure that disabled people are involved and not just on the outside waiting for someone to talk to [us].”

As cliche as it sounds, your attitude about your circumstances can also impact your overall sense of wellbeing.

That’s not to say that you can’t have bad days, or that you should pretend to be happy when you’re not.

Having a disability is hard. However, having a generally positive outlook can lower stress levels and boost your happiness.

Brittany Ferri, an occupational therapist who owns her own practice, works with clients who are experiencing both psychological and physical symptoms.

She says to me:

“It is our reaction to this loneliness that determines how our lives will be impacted. This makes it especially important for individuals with disabilities to receive the support, care, and resources that they need to successfully manage the symptoms of a condition while continuing to live their lives in a meaningful and productive manner.”

Know The Differences Between Loneliness and Depression

Sometimes, loneliness and depression are hard to differentiate, especially since loneliness is a symptom of depression for many people.

Feeling like a burden, though also a common experience for disabled people, is another symptom of depression.

Since having a disability increases the likelihood of a person experiencing depression, it’s especially important for disabled people to keep a check on their mental health and to know the signs and symptoms of depression.

Brittany Ferri, the occupational therapist, notes that disabled people should take the time to check in with themselves regarding their emotional and mental health.

“Whether an existing or newly diagnosed disability, a chronic illness or medical condition can have a major impact on a person’s emotional health,” she tells me.

“If left unaddressed, these emotional effects can cause cognitive changes and a decline in mental health, leading to conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders, stress-related disorders, and more.”

If you do find yourself experiencing symptoms of depression or other symptoms of mental illness that are impacting your ability to function daily, don’t hesitate to contact your doctor.

Closing Thoughts

Loneliness isn’t an uncommon experience for disabled people, and it’s okay to feel lonely sometimes.

As a disabled person, there are a multitude of reasons you may feel lonely, and it’s important to understand why.

Are you isolating yourself? Are societal barriers making the world difficult to access? Or, is your loneliness a symptom of depression?

Just because you’re more likely to feel lonely at times as a disabled person doesn’t mean you’re doomed to feel lonely forever.

Realizing that you may be isolating yourself from others, or that you’re isolated due to inaccessibility is difficult — and you can’t always fix these issues immediately or on your own.

However, by taking the time to understand why you feel lonely, you can begin to take the first steps towards feeling a little less alone.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of The Roots Of Loneliness Project, the first-of-its-kind resource that comprehensively explores the phenomenon of loneliness and over 100 types we might experience during our lives.

Find Help Now

If you’re struggling with disability loneliness, we’ve put together resources to meet you wherever you are — whether you want someone to talk to right now, or are looking for longer-term ways to help ease your loneliness.

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255); Deaf or hard of hearing dial 711 before the number or connect via online chat

- Resources & Emotional Support For Loneliness

- Volunteer & Pet Adoption Opportunities